Changing a plan at the last minute is one of the surest ways to create confusion and cause a mission to fail. Before I became a fighter pilot, I didn’t realize how much time and effort went into mission planning. It’s meant to be a joke, but it’s surprisingly accurate that mission planning takes as long as you have.

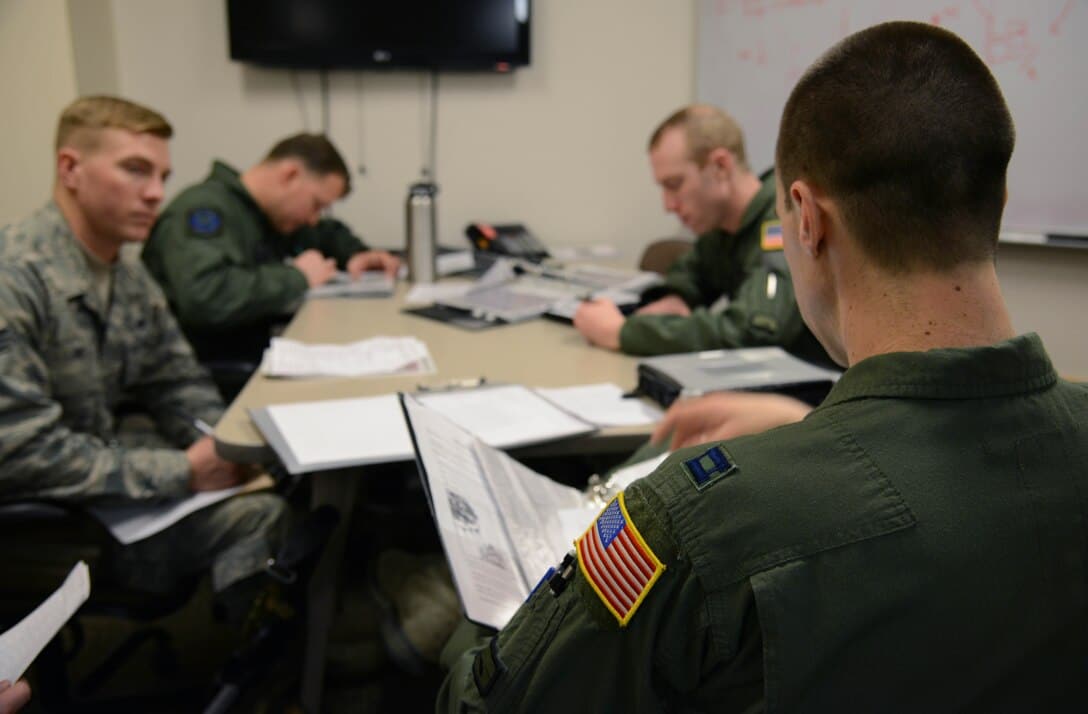

Often, during large force exercises, we’ll be flying with upwards of a hundred aircraft. Because no plan survives first contact with the enemy, the mission commander is almost always a fighter pilot, on the leading edge, ready to adjust the plan as the mission develops. The commander is also in charge of organizing and leading the planning in the days before the mission.

The “stick and rudder” traits required to dogfight—prioritization, decisiveness, confidence—carry over to mission planning, however the hard skills required to lead hundreds of people through the mission planning process are technical and must be practiced.

Similar to managing projects in the civilian world, we must refine objectives, develop a plan with limited resources, and execute it in a dynamic environment. Over the years we’ve developed hundreds of best practices to make the process as smooth and efficient and possible. One of them is the GICL, or Good Idea Cut-off Line.

When the mission planning begins there are usually several objectives that are set at a high-level, but the “how” is essentially a blank slate. As hundreds of people work through the process, a plan gradually begins to take shape. New ideas are constantly brought up and debated as the plan evolves. However, the timeline will always have a GICL, usually about two-thirds of the way through, after which the plan will be set and no major changes will be allowed.

It can be counterintuitive to not accept better ideas. Who wouldn’t want a plan that better optimizes fuel, or one that maximizes firepower? However, late changes to the plan almost always results in confusion and suboptimal performance. 99% of the time, we don’t have the option to push the mission to a later date; it’s usually just one part of a much larger war effort. This means that everyone—from the mission commander to the most junior enlisted—must deeply understand their roles before the end of the planning process.

After the GICL, the foundation of the mission is set. Everyone should be on the same page, even if they disagree with certain aspects of the mission. Of course, if there are safety issues, or major flaws in the plan, they will be brought up and addressed, but barring that, the general plan will remain constant. The reason is that a mission plan is a complex system—it’s nearly impossible to make a major change and not have them ripple throughout all aspects of the plan.

Because there is still work to be done—roles further polished, contingencies accounted for, and individual weapons systems optimized for their specific tasks—large changes in the plan must be given time to settle out. Both in mission planning and outside of flying, it’s easy for people to keep implementing unnecessary changes. The brainstorming process, which is so critical early on, becomes a larger and larger detriment the closer you get to execution. The GICL is a tool we use to put a stake in the ground that lets everyone know the project has changed phases. Give it a shot in your life: with a red pen or marker, write down the time when you will stop adjusting the plan and instead focus on execution.