After recent rumors surfaced that the United States Air Force is testing a new high-performance spy plane developed by Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works, Sandboxx News decided to explore the possibility that the legendary hypersonic SR-72 may not only be real, but potentially heading toward service in the not too distant future.

Recently, Sandboxx News discussed remarks made by Vago Muradian, the editor-in-chief of the Defense & Aerospace Report, during an episode of the outlet’s podcast. During a conversation with Teal Group Senior Analyst J.J. Gertler, Muradian brought up the Air Force’s highly classified RQ-180 reconnaissance drone, before going on to state that the Air Force was already testing “a much more capable reconnaissance aircraft that is the product of the Skunk Works.”

“My understanding is that the program was re-scoped because it is that ambitious a capability that [it] required a little bit of re-scoping in order to be able to get to the next block of aircraft,” Muradian said.

With no further details to pull from, these remarks could potentially point to any number of secretive Special Access Programs (or SAPs, as classified efforts are commonly called), but through extensive research and several interviews, we believe these statements could indeed align with what we know about the SR-72 that Lockheed Martin was once openly developing.

For more context into Muradian’s claims and a thorough exploration of the turbine-based combined-cycle hypersonic propulsion system that was developed for the SR-72, we recommend reading that previous article. In this installment, we’ll delve into the known and alleged timeline associated with this aircraft’s public – and then covert – development.

Related: SR-72? Hints of a new Skunk Works spy plane reignite rumors of a Blackbird successor

The Air Force did not have an SR-71 replacement when the Blackbird retired

Legends of a faster, higher-flying replacement for the SR-71, commonly called the SR-72, first began to emerge back in the 1980s when the Blackbird first flew into retirement. Many argued then (and still do today) that the US wouldn’t retire the Mach 3 spy plane without an even more capable replacement already in operation. The unpopular truth, however, was that the SR-71’s massive operating costs combined with advancing air defense technologies led many to believe that spy planes were becoming a relic of the past and that the future was in orbit.

The SR-71’s first of two retirement decisions came in 1989, after what Washington Post reporter Patrick Tyler described as a bit of “last-minute horse-trading to apply declining defense budget resources to other Air Force and intelligence satellite programs.” Put simply, the high-flying aircraft’s perceived value was on the decline right alongside the defense spending that kept it airborne.

Further confirmation that a high-flying replacement didn’t already exist came in the aircraft’s 1994 revival and subsequent re-retirement in 1999, followed by another high-profile effort to bring the Blackbird back to duty in the early days of the Global War on Terror in 2001. If the Air Force already had a fleet of more capable spy planes in service, it’s unlikely these efforts would have gotten much, if any, traction.

But the SR-71 program’s zombie-like inability to die also serves as evidence for America’s lasting need for an Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft with the Blackbird’s unique high-speed and high-altitude capabilities. This was a point not lost on the aircraft’s manufacturer, Lockheed Martin.

Related: Hypersonic firm Hermeus proves their Mach 5+ jet engine works

Development on the SR-72 began in 2006

In 2006, the firm secretly began initial design work on what would become the SR-72, but it wasn’t until 2013 that the effort first broke cover. In early November of that year, Lockheed Martin unveiled the SR-72 concept with a media push that included several interviews with Brad Leland – Lockheed Martin’s Hypersonics program manager and the engineer who had already been heading the effort for seven years by that time.

“Hypersonic aircraft, coupled with hypersonic missiles, could penetrate denied airspace and strike at nearly any location across a continent in less than an hour,” Leland was quoted as saying in a Lockheed Martin press release that has since been taken down. “Speed is the next aviation advancement to counter emerging threats in the next several decades. The technology would be a game-changer in theater, similar to how stealth is changing the battlespace today.”

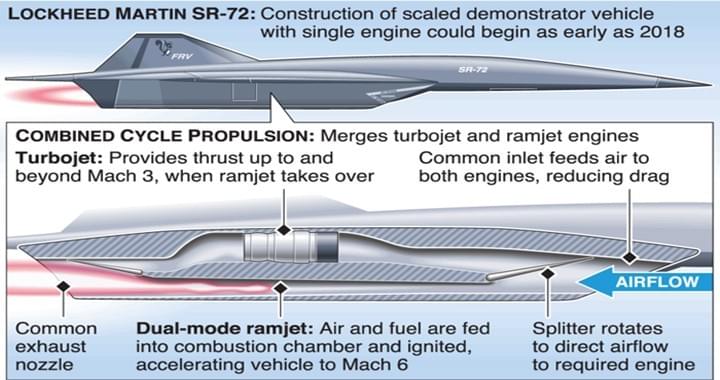

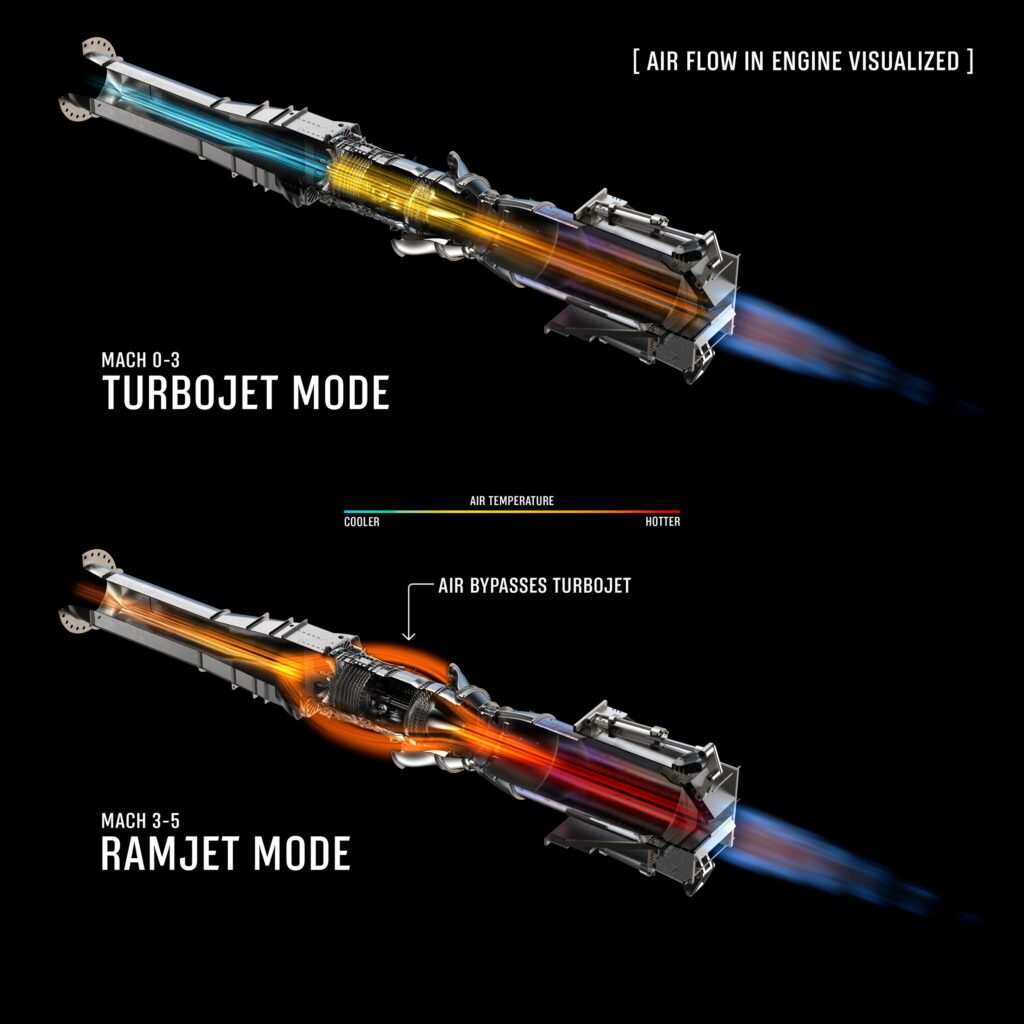

According to Leland, his SR-72 team included 20 Lockheed employees and he was confident that they could build the twin-engine hypersonic aircraft in “five to six years” for under a billion dollars. The program had already zeroed in on the idea of using a turbine-based combined cycle engine (TBCC) thanks to the previously canceled HTV-3X program that had similar hypersonic aims. Lockheed Martin partnered with engine manufacturer Aerojet Rocketdyne to develop just such an engine with the stated aim of reaching Mach 6 – which Leland said was based on heat-withstanding material costs rather than limitations of their proposed propulsion system.

“The turbine, which works well up to Mach 2, and the scramjet (supersonic combustion ramjet) work well at Mach 4 and above. By making those work together down at Mach 3 – below Mach 3 – that’s really the key,” Leland told USNI News at the time.

While details about the scramjet were not forthcoming, Leland did confirm that the two turbofan engines in consideration to serve as the turbine basis for their TBCC propulsion system were the Pratt & Whitney F100 and the General Electric F110. Both are afterburning high-performance engines that had already seen service in American fighters like the F-15 Eagle and F-16 Fighting Falcon.

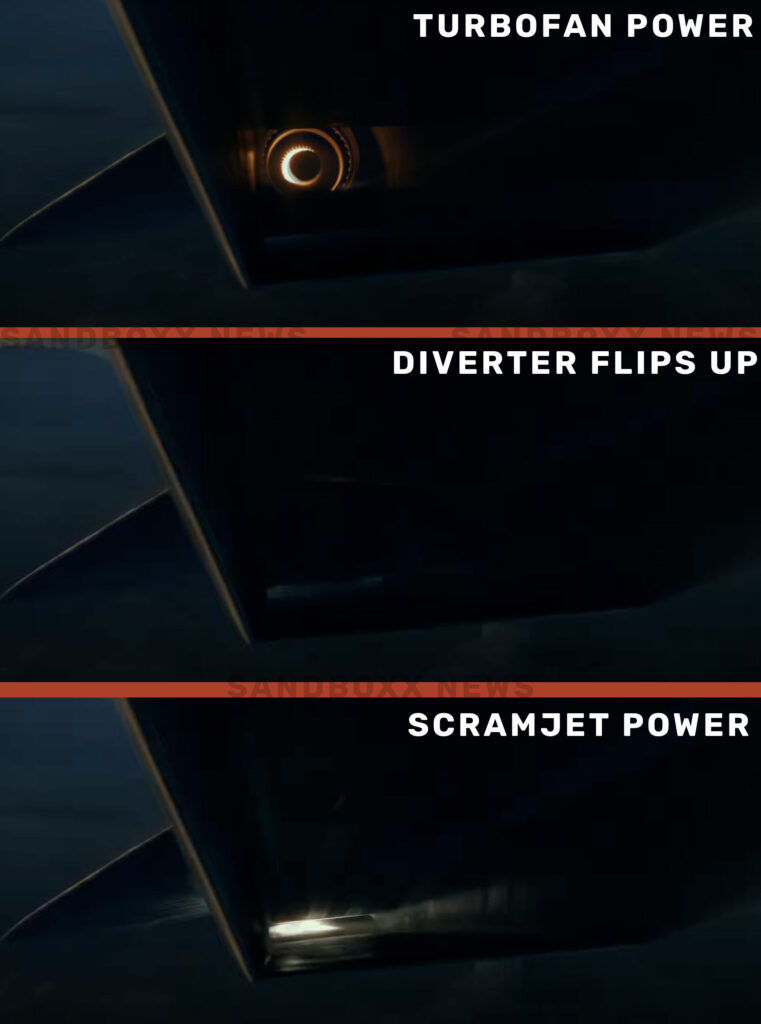

“We’re looking at dual flow-paths, an over and under configuration,” Leland said, highlighting the intended layout for the turbofan and scramjet.

This approach diverges from ramjet-centered hypersonic TBCC efforts like today’s Chimera engine made by Atlanta-based hypersonic startup, Hermeus. Chimera uses a turbojet placed in front of a ramjet, so at high speeds, the turbojet itself becomes the blocking body that slows airflow to more manageable subsonic speeds. Because a scramjet operates with supersonic airflow, Lockheed couldn’t place the turbofan in-line with the scramjet and instead positioned it either above or below it to allow for unobstructed airflow.

You can see this concept demonstrated in the 2022 movie Top Gun: Maverick when the fictional Darkstar transitions from turbofan to scramjet modes, which goes to show how established the concept already was. Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works, of course, designed the fictional Darkstar for the movie.

Leland said Lockheed Martin had a “very solid design” for the aircraft, but would take at least three more years (and an influx of cash) to prove they could marry a turbofan to a scramjet in a truly functional manner. That would then lead to a single-engine flying demonstrator, which he said would be about the size of an F-22 Raptor and could be flying by 2018. A twin-engine operational aircraft based on that design would follow suit by 2030.

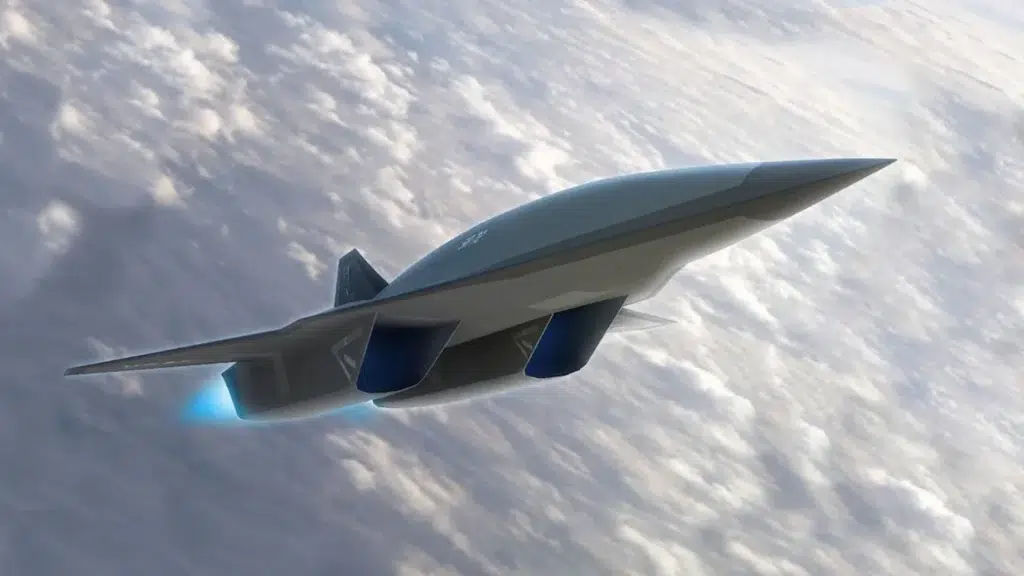

During this 2013 media push, Lockheed Martin launched a page for the SR-72 on its website that included a render of the aircraft in flight and links to press releases and media coverage about the new highly publicized effort.

Related: 5 secretive new warplanes the US is developing for the next big fight

Lockheed Martin was open about the SR-72’s progress by 2015

In 2015, the SR-72 once again drew headlines after a Popular Science cover story devoted to the program offered new – and arguably inaccurate – details about the aircraft’s progress. According to this article, the turbine-based combined cycle engine Leland had discussed in 2013 was now meant to operate in three distinct “modes” – first flying under turbojet power before transitioning to ramjet power, and then finally, to the scramjet.

Turbojets, it’s worth noting, are a different and older type of jet engine from the turbofans Leland described in 2013, but it’s likely this word choice was a simple editorial error. As for writing that the engine employed both ramjet and scramjet modes – that may have been a creative description for the complex transition from turbofan to scramjet power, highlighting the use of a diverter between inlet flow paths to slow inflowing air to subsonic speeds within the scramjet (allowing it to temporarily function like a ramjet).

This concept is more traditionally called a dual-mode scramjet, and has become the de facto expectation for any combined cycle propulsion system aiming to bridge the velocity gap between turbofan and scramjet optimum operating speeds. Dual-mode scramjets also played an important role in Aerojet Rocketdyne’s Rocket-Based Combined Cycle (RBCC) engine designs from the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Turbojets notwithstanding, Lockheed Martin proudly updated its SR-72 webpage to reflect this new cover story, including an image of the magazine cover alongside the previously published quotes from Leland.

The company also included this statement, doubling down on the timeline Leland had laid out two years prior: “A hypersonic plane does not have to be an expensive, distant possibility. In fact, an SR-72 could be operational by 2030.”

Lockheed Martin also released a promotional video in late 2015 that included a brief clip of what appears to be its SR-72 design along with the phrase, “Global Strike.” This may have been the first time Lockheed Martin formally acknowledged the idea that its hypersonic SR-72 wasn’t strictly oriented toward reconnaissance missions, and instead, would be designed to deliver ordnance as well.

Related: Lasers won’t save us from hypersonic weapons

In 2017, Lockheed Martin said the engine was ready to fly (and according to eyewitness reports… already was)

In 2017, Lockheed Martin once again courted media exposure for the SR-72 program with claims that ground testing of its combined-cycle hypersonic engine had been underway since 2013 and the technology was finally mature enough to be placed into a real aircraft.

“We’ve been saying hypersonics is two years away for the last 20 years, but all I can say is the technology is mature and we, along with DARPA and the services, are working hard to get that capability into the hands of our warfighters as soon as possible,” Rob Weiss, Lockheed Martin’s executive vice president and general manager for Skunk Works, told Aviation Week in June 2017.

Weiss claimed the Skunk Works was “getting close” to beginning development of the single-engine full-scale Flight Research Vehicle (FRV) that he also described as about the size of an F-22 Raptor. This single-engine demonstrator was set to start flying by the early 2020s, and Weiss once again affirmed 2030 as the target for a twin-engine platform to enter operational service.

But just a few months later, in September of 2017, eyewitnesses reported seeing a small-scale SR-72 technology demonstrator (or Flight Research Vehicle) flying over Palmdale, California. This is where Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works Division as well as the Air Force’s classified aircraft manufacturing facility, Plant 42, are located. It is also the same location where Northrop Grumman’s B-21 Raider was spotted making its first test flight just weeks ago.

These reports prompted Aviation Week to reach out to Lockheed Martin’s Orlando Carvalho, executive vice president of aeronautics, at the time. Carvalho was not forthcoming with confirmation but seemed to go out of his way not to deny the eyewitness reports either.

“Although I can’t go into specifics, let us just say the Skunk Works team in Palmdale, California, is doubling down on our commitment to speed,” he told Aviation Week in 2017.

“Hypersonics is like stealth. It is a disruptive technology and will enable various platforms to operate at two to three times the speed of the Blackbird… Security classification guidance will only allow us to say the speed is greater than Mach 5.”

While this statement was meant to offer little in the way of details, it was the first time Lockheed Martin officials seemingly acknowledged that the program may not longer be limiting the SR-72’s intended speed to Mach 6. “Two to three times” the speed of the Blackbird, while potentially just casual hyperbole, would suggest a top speed of Mach 6.4 at least, and potentially as high as Mach 9.6 or higher.

Related: New footage shows B-21 Raider’s historic first flight

In early 2018, Lockheed Martin officials said the SR-72 was already flying

With rumors swirling about a subscale technology demonstrator already flying with Lockheed Martin and Aerojet Rockeydyne’s combined-cycle engine onboard, Lockheed Martin officials opened 2018 with a hypersonic bang.

In January 2018, Lockheed Martin’s Vice President of Strategy and Customer Requirements in Advanced Development Programs, Jack O’Banion, spoke at the SciTech Forum, held by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics in Florida. During the event, O’Banion projected an artist’s rendering of the SR-72 and discussed the aircraft as though it already existed and had been seeing successes in testing.

“Without the digital transformation, the aircraft you see there could not have been made,” O’Banion told the audience. “We couldn’t have made the engine itself — it would have melted down into slag if we had tried to produce it five years ago. But now, we can digitally print that engine with an incredibly sophisticated cooling system integral into the material of the engine itself, and have that engine survive for multiple firings for routine operation.”

These statements about the TBCC engine could be attributed to the testing we know Lockheed Martin and Aerojet Rocketdyne conducted between 2013 and 2017, but when pressed about these statements by Bloomberg’s Justin Bachman, O’Bannion doubled down.

“The aircraft is also agile at hypersonic speeds, with reliable engine starts,” he stated unequivocally.

But just two months later, a speech delivered on the opposite side of the world would seemingly thrust the SR-72 effort back into the shadows, where it’s remained ever since.

Related: Why Russia’s Mach 3.2 MiG-25 couldn’t catch the Blackbird

The SR-72 program suddenly went dark just as the hypersonic arms race began

On March 1, 2018, Russian President Vladimir Putin delivered what has since become an infamous speech, in which he announced what he claimed to be the world’s first operational modern hypersonic weapon, the Kh47M2 Kinzhal, along with Russia’s plans to field the nuclear Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV). This address has since been seen by many as the onset of the modern hypersonic arms race.

“No one has listened to us,” Putin exclaimed. “You listen to us now.”

Of course, we would later learn that the Kinzhal missile – like the Russian military as a whole – was not nearly as capable as Putin claimed, but at the time, these new weapons seemed to present a serious threat to the United States. And worse still, it was a threat the US had no means to match.

After leading the world in hypersonic technology with programs like NASA’s X-43 and Boeing’s X-51, the US shifted its focus away from advanced systems meant to deter neer-peers throughout two decades of the Global War on Terror. With no publicly disclosed American hypersonic weapons programs in development, let alone in service, Putin’s speech seemed to suggest that America’s old Cold War foe had managed to leapfrog the US in this realm of advanced weapons technology.

And just like that, the SR-72 program disappeared.

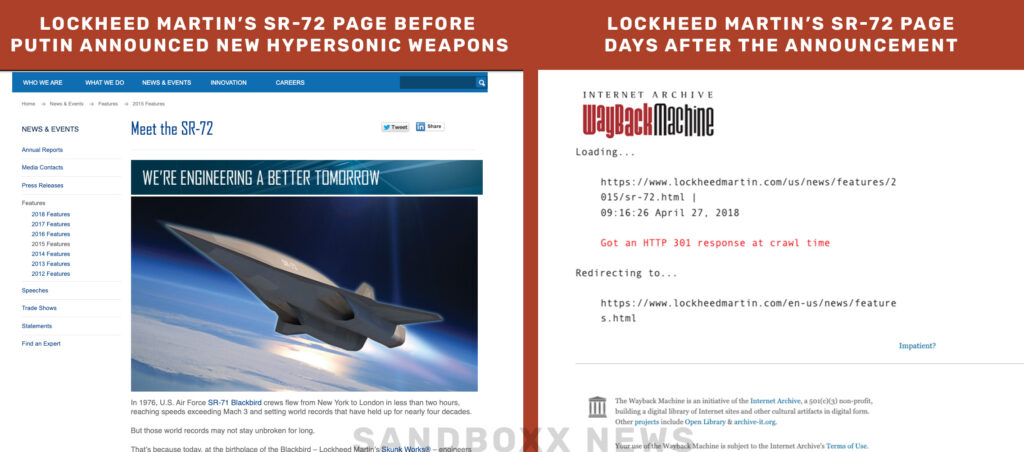

Within days of Putin’s speech, as the world’s media exchanged headlines about hypersonic missiles, Lockheed Martin quietly took down the SR-72 webpage that had been up for five years to that point and redirected the URL to its press releases page. All press releases about or even mentioning the SR-72 program were purged from their press release archive.

It was as though the entire effort, which to that point included at least 12 years of work from at least 20 Skunk Works engineers, a partnership with Aerojet Rocketdyne on a propulsion system that underwent at least four years of testing, and what its lead engineer Brad Leland described as “a lot of company money,” just vanished into thin air.

You can now only access Lockheed Martin’s SR-72 page using the Wayback Machine (an internet archive that saves old websites). From March 2018 forward, you will find no mention of the SR-72 anywhere on the entire Lockheed Martin website.

Related: US announces successful test of its first fight-ready hypersonic missile

After going dark, hints about the SR-72 Flight Research Vehicle still occasionally bubbled to the surface

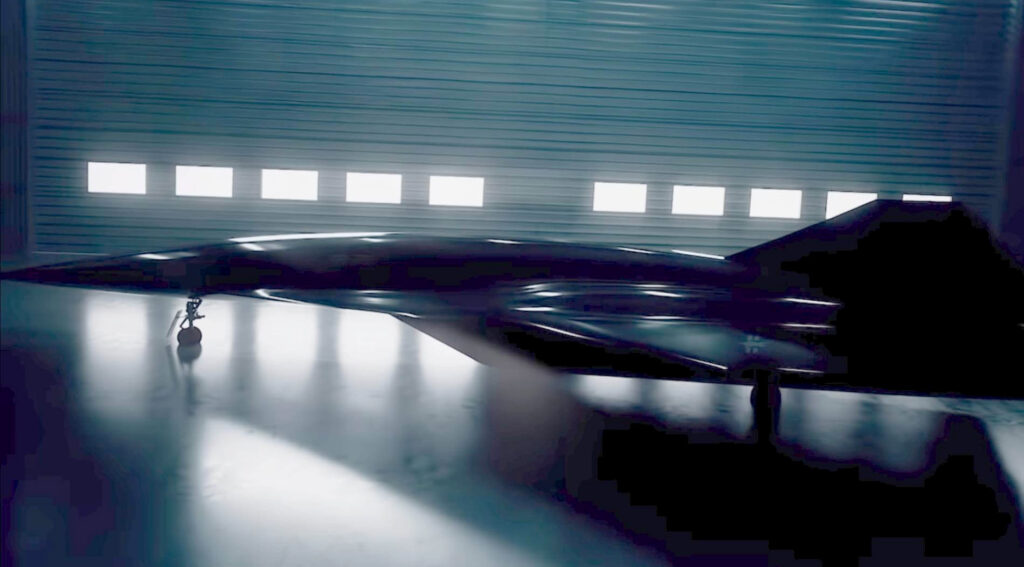

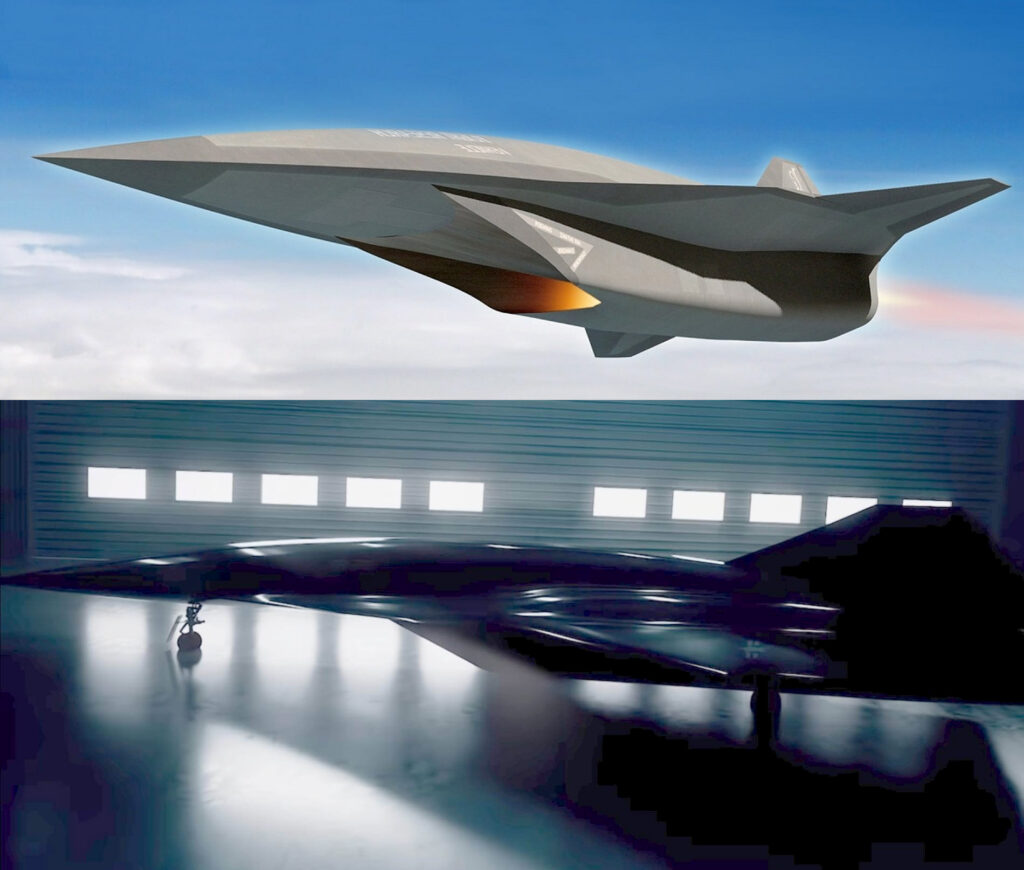

Despite the SR-72 effort going dark, a video released in 2021 by the Air Force’s Profession of Arms Center of Excellence offered us what may be the first real glimpse of the single-engine SR-72 Flight Research Vehicle Lockheed Martin had previously claimed could be delivered by 2018.

A brief clip of what appears to be an uncrewed demonstrator bearing a striking resemblance to renders of Lockheed’s SR-72 can be seen for a few fleeting seconds near the end of the video. The aircraft does not appear to be CGI-generated, and while it could have been nothing more than an expensive prop, that seems like an unlikely expense for a short clip in a public affairs presentation.

Of course, it also seems odd that the Air Force would reveal such a classified effort in a promotional video, but based on Muradian’s comments we already discussed, the program needed to be re-scoped after the delivery of the first test articles.

Revealing this brief snippet of the SR-72 FRV (if that is, indeed what is seen in the video) could have been meant as a winking message to national adversary nations already fielding hypersonic weapons the United States publicly had no means to match. Or, if the program was in question before being re-scoped, the brief reveal may have been seen as a minimal security risk.

If real, this brief clip shows the effort was ongoing, or at the very least, had resulted in delivered test articles by 2021.

Related: Why America’s new NGAD fighter could be a bargain, even at $300 million each

China allegedly thought Top Gun’s Darkstar was real… Did they have a good reason?

In 2022, Top Gun: Maverick flew into theaters with an unusual new aircraft in tow – an experimental hypersonic technology demonstrator powered by a turbine-based combined cycle engine designed and built by Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works.

And that’s not just a line in the script – it’s reality.

“The reason it looks so real is because it was the engineers from Skunk Works who helped us design it,” the film’s director, Joseph Kosinki told Sandboxx News before the movie’s opening. “So those are the same people who are working on real aircraft who helped us design Darkstar for this film.”

The resulting Skunk Works mock-up was so realistic, producer Jerry Bruckheimer told us, that it allegedly even managed to fool China’s intelligence apparatus.

“The Navy told us that a Chinese satellite turned and headed on a different route to photograph that plane. They thought it was real. That’s how real it looks,” Bruckheimer first told Sandboxx News.

Re-orienting a spy satellite is no small matter. These immensely expensive orbital platforms can only carry a limited amount of fuel onboard and there is currently no way to refuel them in orbit. This means that any time a satellite is forced to expend fuel to adjust its orbit or orientation, it directly shortens its operational lifespan.

If Bruckheimer’s story is true, it seems unlikely China would sacrifice the precious fuel of a high-end spy satellite over a movie they already knew was in development.

But, China may have been willing to expend some valuable fuel to get a peek at a real aircraft that its intelligence apparatus already knew was in development or testing… Maybe even one that bore a striking resemblance to the Darkstar itself.

Top Gun: Maverick began filming in May of 2018 – eight months after witnesses first reported seeing an SR-72 demonstrator flying over Palmdale, four months after Lockheed Martin executive Jack O’Banion said their SR-72 FRV was flying, and just two months after the program went dark.

Related: Spy satellites aren’t nearly as all-seeing as you think

Lockheed Martin uses Darkstar to not-so-subtly hint at real capabilities

To be clear, Bruckheimer’s spy satellite claim may have been a bit of creative storytelling meant to sell the movie to airplane nerds like us, but claims about the realism depicted by the Darkstar were not limited to Hollywood. Lockheed Martin soon rolled out a marketing campaign of its own that was ripe with not-so-subtle hints about just how feasible the technology might be.

On March 12, 2023, Lockheed Martin tweeted an image of the SR-71 in a hangar along with a caption that said, “The SR-71 Blackbird is still the fastest acknowledged crewed air-breathing jet aircraft.”

Highway to The Danger Zone #RealTopGun

— Lockheed Martin (@LockheedMartin) March 12, 2023

The SR-71 Blackbird is still the fastest acknowledged crewed air-breathing jet aircraft. #Oscars pic.twitter.com/62Xqr62gze

The word acknowledged stands out for good reason, as it suggests there may be faster record-holders that have yet to be disclosed to the public. Things got even juicer when Lockheed Martin put out a press release that said this:

“With the Skunk Works expertise in developing the fastest known aircraft combined with a passion and energy for defining the future of aerospace, Darkstar’s capabilities could be more than mere fiction. They could be reality…”

It was evident that Lockheed Martin was not shying away from comparisons between Top Gun’s Darkstar and its own SR-72 program, though, to this day, there is still not a single mention of the SR-72 anywhere on their website, even amid the flurry of Darkstar-related promotional materials.

In another statement that has since been removed from Lockheed Martin’s Darkstar materials, the company seemed to even say the quiet part out loud:

“Darkstar may not be real, but its capabilities are. Hypersonic technology, or the ability to travel at 60 miles per minute or faster, is a capability our team continues to advance today by leveraging more than 30 years of hypersonic investments and development and testing experience.”

And this brings us up to the present day, and the recent claims made by Vago Muradian. In a future article, Sandboxx News will compare what we learned from this timeline to Muradian’s comments and other known technological breakthroughs, before drawing our conclusion.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- Operation Olympic Games: The first cyberweapon

- The favorite games of BUD/S instructors that SEAL candidates suffer through

- Garrett STAMP – The Marines nearly got a weird flying jeep during the Cold War

- Appearance is everything in the age of digital warfare

- F-35 versus A-10 showdown revived as new documents come to light