Last Sunday, a Marine Corps F-35 crashed over South Carolina under seemingly mysterious circumstances. The pilot, who has not been identified, was forced to eject for unknown reasons, but the aircraft didn’t simply crash immediately after as one might expect. Instead, the $100 million stealth fighter continued flying for about 60 miles before ultimately crashing near Indiantown, South Carolina.

Despite many outlets reporting the lost F-35 as an “80 million” aircraft, the specific variant of this stealth fighter, the F-35B, actually rings in at around $101.3 million. Unlike the approximately $80 million F-35A, which needs long, well-manicured runways to take off and land, the F-35B is a short take-off/vertical landing fighter. In other words, this version of the F-35 can hover and even land vertically, driving up the cost by a fair margin.

And if getting the price of the aircraft wrong by $20 million or so seems egregious, when it comes to quickly popularized misconceptions related to this story, it’s only the tip of the iceberg.

Despite officials asking the public for help on social media, it ultimately took over 24 hours to locate debris from the lost F-35. By then, the story had become a trending topic across the internet’s myriad social media platforms.

Some expressed anger and frustration.

“How in the hell do you lose an F-35?” Representative Nancy Mace (R-SC) wrote on X (previously known as Twitter). “How is there not a tracking device and we’re asking the public to what, find a jet and turn it in?”

Others took the opportunity to create some downright funny memes.

And of course, many others took the opportunity to inject conspiratorial thinking into the mishap, with social media accounts and less-reputable news outlets advancing theories about artificial intelligence gone haywire, Chinese hackers taking control of the aircraft, and more. Before debris from the F-35 was found (and even after), many social media commenters were even claiming that the aircraft itself had flown all the way to Cuba, where it had landed safely and would soon be reverse-engineered by Russian operatives.

Of course, the only evidence for any of these theories often came in the form of TikToks of older guys in flat-brimmed hats yelling, “Come on, think about it!” from the drivers’ seats of their pickup trucks… But that hasn’t stopped many of these theories from taking root in the conspiracy-peddling corners of the internet.

So let’s delve into what we know happened, what information we’re still waiting on, and when we’re likely to find out about the rest.

Related: These are the 3 different aircraft we call the F-35

The lost F-35 timeline

Two U.S. Marine Corps F-35Bs hailing from the Marine Fighter Attack Training Squadron 501 (VMFAT-501) with the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing departed from Joint Base Charleston on Tuesday to conduct what Captain Joe Leitner, spokesperson for the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing described as a “routine training flight.”

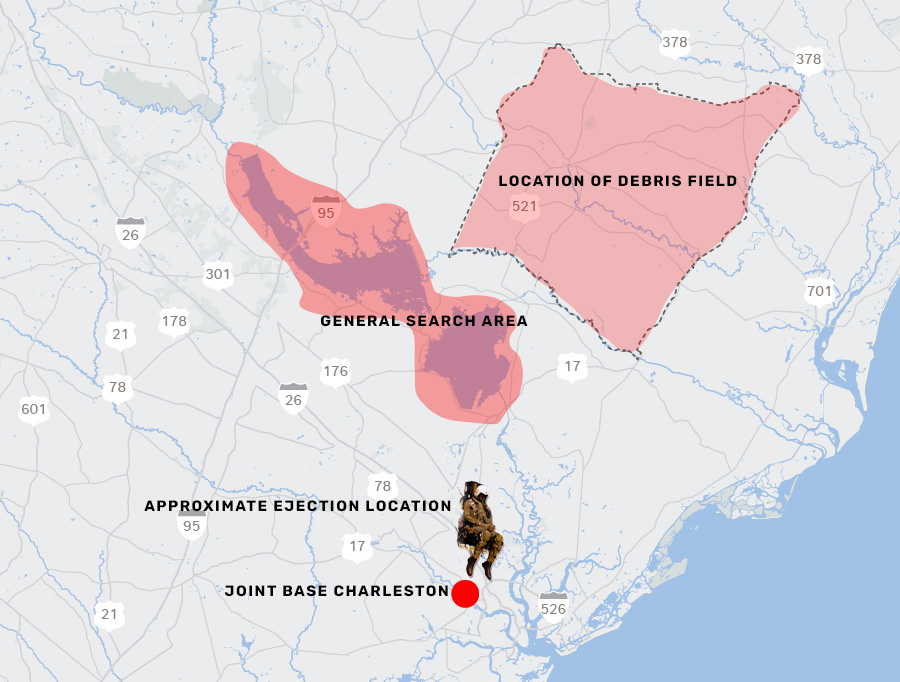

At approximately 2:00 PM EST, one of the two pilots was forced to eject from the aircraft while operating not far from the Lake Moultrie and Lake Marion areas near Charleston, South Carolina. After ejecting, the pilot parachuted safely into a residential neighborhood in Charleston. According to reports, the aircraft’s transponder was malfunctioning and the jet itself was on autopilot at the time of the ejection.

The pilot was immediately taken to a local hospital for evaluation, where he was listed in stable condition. According to an allegedly recorded phone call to Charleston County Emergency Medical Services that was later posted online by a local meteorologist, bad weather may have played a role in the mishap.

“He’s unsure of where his plane crashed, said he just lost it in the weather,” the caller on whose property the pilon landed can be heard saying in the recording.

This account has not been confirmed by Defense officials, and it’s worth noting that the weather in Charleston, South Carolina was listed as 87 degrees and sunny at the time of ejection. Of course, that isn’t to say that unusually strong winds or cloud cover at higher altitudes could have had an effect on the aircraft.

A search effort immediately ensued in the vicinity of Lake Moultrie and Lake Marion, where more than 160,000 acres of lake are surrounded by sprawling expanses of swamps, campgrounds, and rural woods.

Shortly after 5:00 P.M. EST, Joint Base Charleston turned to social media to announce the pilot’s safe ejection and to request help locating the lost F-35.

We’re working with @MCASBeaufortSC to locate an F-35 that was involved in a mishap this afternoon. The pilot ejected safely. If you have any information that may help our recovery teams locate the F-35, please call the Base Defense Operations Center at 843-963-3600.

— Joint Base Charleston (@TeamCharleston) September 17, 2023

According to reports, the aircraft’s transponder was not active at the time of ejection, and the fighter was flying in a stealth configuration, meaning it did not have radar reflectors, often called Lunenberg lenses, installed to allow it to adequately reflect incoming radar waves for reliable detection and tracking.

It wasn’t until more than 24 hours later, at approximately 6:30 PM, that officials announced they had located debris from the crash in a rural stretch of Williamsburg County, some 60 miles from the ejection site.

The most prominent question we’ve fielded on this topic over the past week has undoubtedly been, how is it possible to lose a $100 million aircraft? The truth is, the aircraft is easy to lose because it’s so expensive.

Put very simply, aircraft can only be actively tracked in two ways: either by actively broadcasting a signal (via a transponder) or by reflecting a signal broadcast at them (via radar). Let’s address these methods, and why they failed to help us locate this lost F-35.

Related: Iran claims to detect F-35s over the Persian Gulf. Here’s why it could be true

Why couldn’t we track the missing F-35 via its transponder?

The primary means of tracking an aircraft like the F-35 comes from the use of a transponder. Transponders are electronic devices that transmit a unique code, sometimes known as a “squawk code,” to air traffic control assets like ground radar stations and even some satellites. Transponders can broadcast information like current airspeed, altitude, and direction, making them essential for safely managing the 100,000 or more flights that take place over the continental United States each day.

Transponders also play an integral role in the U.S. military’s identification friend or foe (IFF) system used to deconflict complex airspace – in other words, differentiating between good guy and bad guy planes.

According to Defense officials, the transponder in the aircraft was not functioning at the time of the pilot’s ejection for unknown reasons. This led many to presume it may have malfunctioned, which could have been tied to a larger system failure that ultimately forced the pilot to eject. But that’s not the only reason the transponder may not have been online. According to the Federal Aviation Administration’s Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) paragraph 4-1-20:

“When participating in a VFR standard formation flight that is not receiving ATC services, only the lead aircraft should operate its transponder and ADS-B Out and squawk code 1203. Once established in formation, all other aircraft should squawk standby and disable ADS-B transmissions.”

In other words, when aircraft are flying in formation, only the lead aircraft is supposed to have its transponder broadcasting. This is because transponders respond to a ping sent from a ground station, and if all aircraft in formation have their transponders online in close proximity to one another, they’ll all be pinged at the same time and they’ll all broadcast their information back at the same time.

This would result in all of the signals reaching the ground receiver at once and potentially garbling the transmissions.

So, in order to prevent that, only the lead aircraft in the formation is to leave its transponder “squawking.” Assuming the lost F-35 was not the lead aircraft in the two-fighter formation, it would be perfectly appropriate for its transponder to be offline.

Of course, even if the missing F-35 was the lead jet, it’s possible that the transponder was malfunctioning due to the same system failure that forced the ejection, or even that the ejection itself damaged the transponder system.

Why couldn’t we track the F-35 on radar?

Tracking an aircraft on radar becomes a problem when the aircraft you’re trying to track was specifically designed to be difficult to track.

Now, that’s not to say it’s impossible to track stealth fighters like the F-35 on radar. In fact, there are times when these aircraft are intentionally equipped with radar reflectors, commonly called Lunenberg lenses, for precisely that purpose. However, the missing F-35 was flying in a stealth configuration – in other words, without these lenses installed.

Despite what many internet conspiracies suggest, flying in a stealth configuration isn’t a “mode” the pilot can activate while airborne. Lunenberg lenses are installed or removed while the aircraft is on the ground, so the pilot can’t simply switch to stealth mode.

But even without Lunenberg lenses on a stealth aircraft can be tracked. As we’ve covered a number of times in the past, design elements inherent to stealth fighters can sometimes produce a resonance against lower-frequency radar arrays like those used by some air traffic control towers, weather tracking stations, and early warning defenses. These radar arrays are not capable of producing the image fidelity required to guide a weapon into a target – instead, these resonances can sometimes be used to alert air defenders to the presence of a stealth fighter somewhere in a direction, but they can’t lock on to the fighter in order to guide a missile into it.

The truth is, while nations may sometimes brag about being able to detect these low-frequency resonances, doing so reliably is another story.

In other words, stealth fighters are specifically designed to be difficult to detect, track, or target. So, we shouldn’t be surprised when they turn out to be difficult to detect, track, and target.

Related: Did America’s next stealth fighter just get revealed on Instagram?

Shouldn’t the US military have other means of tracking these exotic aircraft?

There are people out there who may be asking themselves, why aren’t there other means of tracking these jets? The answer to that question really comes down to the realities of warfare and people’s common misconceptions about the broad (but still limited) capabilities of today’s technology.

One might contend that $100 million worth of state secrets screaming through a combat zone faster than the speed of sound might warrant a different and more exotic means of transmission than a conventional aircraft transponder, but the truth is, no matter how exotic the signal you’re broadcasting is… broadcasting any signal can make these aircraft easier to detect, track, and target.

Transmitting data of any type, whether voice communications or simply a tracking signal, requires the aircraft to broadcast electromagnetic energy somewhere – usually to another aircraft, a ground station, or a satellite. As a result, these aircraft and the procedures pilots use when they fly them are all about minimizing the possibility of detection via signal transmission.

Adding another transmitted signal meant to help U.S. military forces know the exact location of an F-35 at any given time creates a potential vulnerability for adversary forces to exploit, and as such, just wouldn’t be a clever idea.

Related: The birth of stealth: How defeating radar became the way of war

Could the F-35 have been hacked by China or even AI?

Because the reason the pilot chose to eject has yet to be released, many have seen the absence of confirmed information as an opportunity to advance a variety of exaggerated narratives. One that surfaced almost immediately was the idea that the aircraft had been taken over by hackers – or worse, artificial intelligence – that ejected the pilot without his consent.

These theories are largely built upon very real statements and even reports from watchdogs like the Government Accounting Office that outline the F-35’s vulnerabilities to cyber-attacks and even hacking… But the truth is, none of these concerns have been about the possibility of the aircraft being taken over by an adversary. It’s actually a great deal more nuanced than that.

The primary source cited tends to be a 2018 report from the Government Accountability Office titled Weapon Systems Cybersecurity: DOD Just Beginning to Grapple with Scale of Vulnerabilities.

Of course, despite outlets like The Daily Mail citing this report as substantiation for the hacking theory, none of these articles actually include the title or link to the 50-page report… And that’s likely because the report doesn’t actually substantiate their claim. In fact, the report, which addresses vulnerabilities across the breadth of the defense apparatus, never even mentions the F-35 by name or designation once.

Now that’s not to say that these cyber vulnerabilities were not, or are not, present in today’s F-35s… but it’s important to understand the actual nature of the hacking threat for a platform like the Joint Strike Fighter.

Related: This is what it takes to join military aviation’s most exclusive club

The two primary avenues a hacker might take to gain access to F-35’s onboard systems come in the form of the aircraft’s two primary networked systems. The first, which was in use at the time of that report, was the Autonomic Logistics Information System, or ALIS. ALIS was an automated logistics support system that tracks use, issues, and maintenance requirements for the aircraft to allow for rapid logistics and maintenance support. Hacking into this system could certainly cause serious problems, but not the sort a pilot would need to eject over. Instead, hackers could indicate that the aircraft needed unscheduled maintenance, or gunk up logistical scheduling to slow repairs down and reduce fleet-wide readiness rates.

The ALIS system, however, is being replaced since 2022 with the new and more secure Operational Data Integrated Network (ODIN) logistics information system. That’s not to say ODIN is hack-proof, but faults found in ALIS are no longer a significant concern, and again, hacking ODIN is more likely to result in headaches than ejections.

The other potentially vulnerable network is the Joint Reprogramming Enterprise (JRE) system, which is used primarily for mission planning and to provide important situational awareness to the pilot in combat. The JRE provides vital mission information and receives frequent updates about adversary weapon systems and capabilities and threat information.

As one example of the JRE’s capability set, as an F-35 pilot is approaching a threat like a Russian S-400 surface-to-air missile system, the JRE can provide data about the platform’s targeting envelope (or how close the F-35 can fly without being targeted) to help the pilot avoid unnecessary risks as they traverse the battlefield.

Hacking this system could absolutely create risks – for example telling a pilot they can fly much closer to that S-400 than they actually can. If the pilot were misled by a hacker who infiltrated the JRE, they might fly their aircraft right into a dangerous situation, resulting in being shot down. But again, gaining access to this system is a far cry from gaining control of the aircraft.

Even pilots inside the aircraft are required to enter unique PIN numbers and specified mission authorization codes in order to access the flight controls they’re physically touching.

Of course, in the world of cyber security, it’s hard to say anything is impossible… But when we’re talking about an F-35 flying over the continental United States, hailing from a training command, the most likely culprits would obviously be a system failure or human error. Hacking might be somewhere in a long list of possibilities, but it’s nowhere near the top – and if it did happen, it would likely manifest in a system failure or the pilot misinterpreting information and making a bad decision, rather than the aircraft falling under adversary control.

And of course, since the 2018 report on the Defense Department’s cyber vulnerabilities, a long list of corrective actions have been taken – many with a particular (though largely classified) focus on the JRE.

Related: Offsetting China’s stealth fighter advantage: An in-depth analysis

Could the pilot have been auto-ejected?

There is absolutely no evidence available to date to suggest that the pilot did not choose to eject. This theory is often substantiated by a very loose understanding of how these systems function and, of course, the most common citation levied by social media pundits just yelling… “Come on!” But to be fair to the world’s crazy uncles, it’s actually not outside the realm of possibility.

The STOVL F-35B does indeed have an auto-ejection system linked to its Martin-Baker US16E-type ejection seat. In fact, the F-35B is the only variant of the Joint Strike Fighter to carry this capability due to the unique dangers of conducting short take-offs and vertical landings on platforms like amphibious assault ships. Details about the exact flight parameters that prompt the system to initiate an auto-eject remain nebulous in publicly available sources, but it is confirmed that the ejection seat in all F-35s is tied into the aircraft’s overall flight systems in order to prevent pilots from ejecting in unsafe situations.

However, the auto-eject feature in the F-35B is meant to eject pilots during hover and vertical-landing situations, in which an engine failure could cause the aircraft to rapidly tumble. It’s possible that the auto-eject feature may not even function when the aircraft is not flying in this profile, but it is also possible that the aircraft was hovering at the time of the ejection.

But because the auto-eject function is designed to help pilots survive in the event of an engine failure while hovering, it seems unlikely that the aircraft would have gone on to fly for 60 miles thereafter. While not impossible, it’s far more likely that the pilot chose to eject for a reason that has yet to be disclosed.

Related: Why stealth helicopters are so hard to design

Why did the F-35 keep flying for dozens of miles after the ejection?

The last question we need to resolve is why was the aircraft able to keep flying for 60 or so miles without a pilot onboard?

An aircraft righting itself after the pilot ejects and then continuing to fly for dozens of miles isn’t unheard of and new safety systems installed in aircraft like the F-16 and F-35 make it even more likely. In particular, Lockheed Martin’s Automatic Ground Collision Avoidance System, or auto GCAS.

Perhaps the most widely known instance of an aircraft righting itself after its pilot ejected came on February 2, 1970, when 1st Lt. Gary Foust was flying a training exercise in his Convair F-106 Delta Dart when the aircraft entered what he, and his wingman, believed to be an unrecoverable flat spin. After repeated recovery attempts failed, Foust finally ejected at around 14,000 feet. But the rapid shift in weight distribution after the pilot, ejection seat, and cockpit canopy were all flung away from the aircraft helped the jet transition from a spin into a dive. With air once again flowing over the aircraft’s control surfaces as it was meant to, the aircraft leveled off and continued flying.

As Foust drifted gently to the ground in his parachute, watching his jet now fly off without him, the other F-106 pilot called him over the radio to say, “Gary, you’d better get back in it.” The aircraft continued flying for about 50 miles before making a gentle belly landing in a Montana cornfield – hence its name.

In 1989, a similar incident occurred when a Soviet MiG-23 pilot ejected from his aircraft. In this instance, the MiG continued flying for 500 miles before ultimately crashing into a house in Belgium and killing one person inside.

The F-35 is much more likely to fly for long distances thanks to its Automatic Ground Collision Avoidance System. This system was designed to take control of the aircraft just before it collides with the ground in the event a pilot loses consciousness mid-flight.

As Lockheed explains, “The system consists of a set of complex collision avoidance and autonomous decision-making algorithms that utilize precise navigation, aircraft performance and on-board digital terrain data to determine if a ground collision is imminent. If the system predicts an imminent collision, an autonomous avoidance maneuver – a roll to wings-level and +5g pull – is commanded at the last instance to prevent ground impact.”

Sandboxx News spoke to an F-35 pilot about this possibility. The pilot, who asked to remain anonymous, said it was likely this very system that kept the wayward F-35 airborne long enough to go missing. They described it as the system “not allowing the aircraft to crash.”

Related: We asked AI to create images of top-secret new stealth aircraft

Why do these conspiracies take hold?

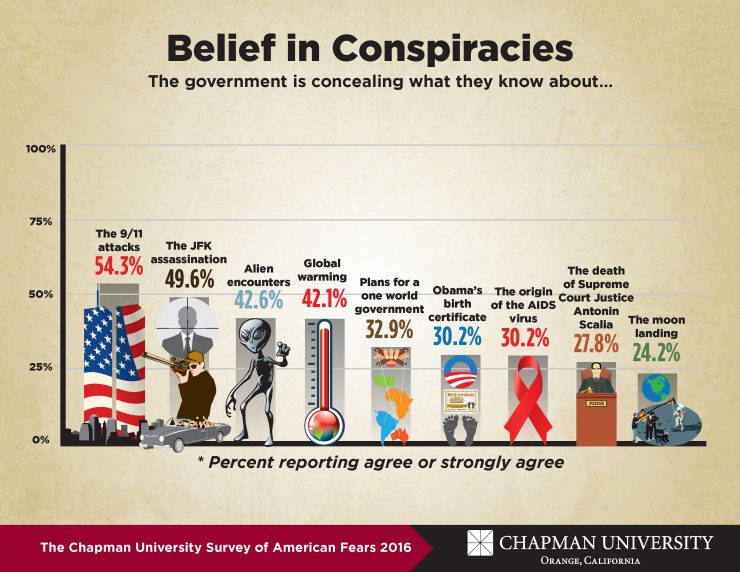

Conspiracy theories have become increasingly mainstream in recent years, to the point where many people tend to prefer their conspiratorial narratives over objective fact-based assessments. Conspiratorial thinking can take root in anyone, regardless of their level of education or place in society.

“Conspiracy theorists are not all likely to be simple-minded, mentally unwell folks – a portrait which is routinely painted in popular culture. Instead, many turn to conspiracy theories to fulfill deprived motivational needs and make sense of distress and impairment,” explained Shauna Bowes, a doctoral student in clinical psychology at Emory University whose peer-reviewed research into conspiracy theories was published in the Psychological Bulletin.

According to Bowes’s research, people are primarily motivated to believe in conspiracy theories because these make the world seem more logical, help the person feel safe, and perhaps most importantly, help them feel as though their community is superior to others’.

An investigation into the root cause of this F-35 mishap is already underway, and the real truth is, many of the questions we have about it may potentially already have answers that, thus far, Uncle Sam has yet to share. After all, we’re talking about the most advanced fighter on the planet and a program that represents an investment of $1.7 trillion or more across more than a half-century. The military’s first priority is not making sure TikTok knows all the details of this mishap. Its first priority is determining the cause of the incident, assessing any risks that cause may represent to the F-35 fleet at large, and mitigating or correcting that risk as expediently as possible.

Whether this mishap was caused by a serious system flaw that had yet to manifest or by simple human error or anything in between – the Pentagon’s responsibility is to ensure the safety of its service members and the combat efficacy of its systems. That means conducting a thorough investigation and only telling the public what it can without running the risk of compromising operational security.

The F-35 pilots Sandboxx News spoke to on background for this story, as well as the long list of aviators and subject matter experts I interact with on a day-to-day basis, all seem sure of one thing: A pilot ejecting and his F-35 going missing over South Carolina sure is a crazy story, but nothing about what’s been revealed so far defies logical explanation.

The only truly mysterious phenomenon associated with this story so far is modern digital culture’s infatuation with conspiracy.

Read more from Sandboxx News

- What are the EFP bombs that are now used in Ukraine?

- Russia’s Black Sea commander alleged dead after strike against fleet’s HQ

- Airpower en masse: America’s new approach to warfare

- Ukraine’s counteroffensive is making some progress but it can’t afford to halt

- Incredible mortar-assembly challenges with the Green Berets